Since moving to Berlin in the early 2000s, I have lived in many areas of town. This, in fact, may be an understatement. During my most nomadic year, I may have lived in four different places. Berlin had not yet become a major tourist destination, most of us lived without the Internet (not to speak of AirBnB), gentrification was something allegedly happening in far-away places and evictions were unheard of. As surreal as it may sound, given today’s ever-increasing housing crises, in those days, there was a considerable faction of denizens who moved around because it was fun. We claimed new habitat for the thrill of it, driven by an appetite for a new outlook on life.

Although itinerant lifestyles may exist anywhere, in Berlin local history encouraged our wanderlust. During the Cold War, the city was defined by lingering conflict, a situation far too delicate to achieve sustained success with real estate investment. For about a decade after the fall of the Wall, it seemed that property development would never catch up. The ordinary tenant competed with squatters rather than with capital for housing. This changed drastically in subsequent years, yet at the time, it meant that affordable living space was plentiful. Granted, the housing conditions did not meet modern standards. One would have to cope with coal heating systems, toilet facilities located across staircases, and no insulation whatsoever. But that didn’t stop us from exploring.

Keeping this habit over the years, it has become an inside joke to say, “I used to live around the corner.” Wherever I am in te city center, this is very likely the case.

Moving within a city makes for a change of scenery, but it is still very different from moving away from one. This is particularly true when one moves back to the vicinity of places one has lived in in the past – as one is bound to do with this kind of affliction over time. Being based in a new location every year or so, my understanding of the city gradually shifted. “I used to live around the corner” – The sentence articulates a sense of belonging that is still part of my present-day experience. Having been local in so many parts of town, I came to think of the city in thoroughly domestic terms.

Peculiarly, the Berlin cityscape, too, encourages residents to form more intimate relationships with their neighbors and surroundings. The condensed residential housing structure in the city’s center – called Wilhelminian, after the German Kaiser of the period in which it was built – once provided space for many more people per square mile than most other Western-European cities of comparable size. Typically, commercial units are tucked into the basements of housing complexes, and domestic life revolves around the infrastructure one finds within walking distance. As a friend once put it: “I can’t really recommend any of these shops, but I rarely see the point of walking the extra mile to get my groceries.”

This profoundly local trajectory shapes much of what it means to be a resident of Berlin’s inner city. The sentiment is thus ingrained in our experience, Berliners have their own term to articulate their sense of belonging to their slice of town. As with much vernacular, the point of reference in this word, ‚Kiez,‘ is not entirely defined. The entity one refers to as a Kiez (or, more appropriately, in connection with a possessive pronoun: my Kiez) can be a street, a block, or even an entire neighborhood. Much more importantly than its object of reference, the term denotes a mentality that conceives of the city as an extension of one’s living room.

That Berlin vernacular should provide its own term for such an outlook on life is rather counterintuitive. One’s secret attachments to the local falafel joint, the web of evening strolls tying one’s identity to a slice of town – this perspective on urban life seems in stark contrast with the narrative of Berlin’s political history. It is the story of a city subdued by a jaw-dropping procession of empires and world views: Berlin was the capital of the German Kaiserreich until 1918; the Weimar Republic until 1933; and the Third Reich until 1945. The city went through four years of occupation after the Second World War and then became the divided border town of the Cold War factions in 1949. Almost a decade after Germany reunited in 1990, the government moved back to town. Finally, with the inauguration of the treaty of Lisboa in 2009, the reestablished capital joined the greater European federal structure. In other words, this city has been host (and pawn) to eight political systems within less than a century. Each of those regimes came with a new set of ideological narratives that the city was to represent. Most notably, during the Cold War, Berlin had to simultaneously perform as the outpost of the ‚free‘ capitalist world as well as the prime example of a territory ‚liberated‘ by the socialist revolution. This is the exact same location where German fascist rulers had feverishly dreamt of erecting not just a country’s but the world’s capital city barely a decade earlier.

How did the other narrative sustain itself in light of such vicissitudes? How is it that Berliners, of all people, fancy conceiving their personal relationship with their neighborhood as formative to what a city is?

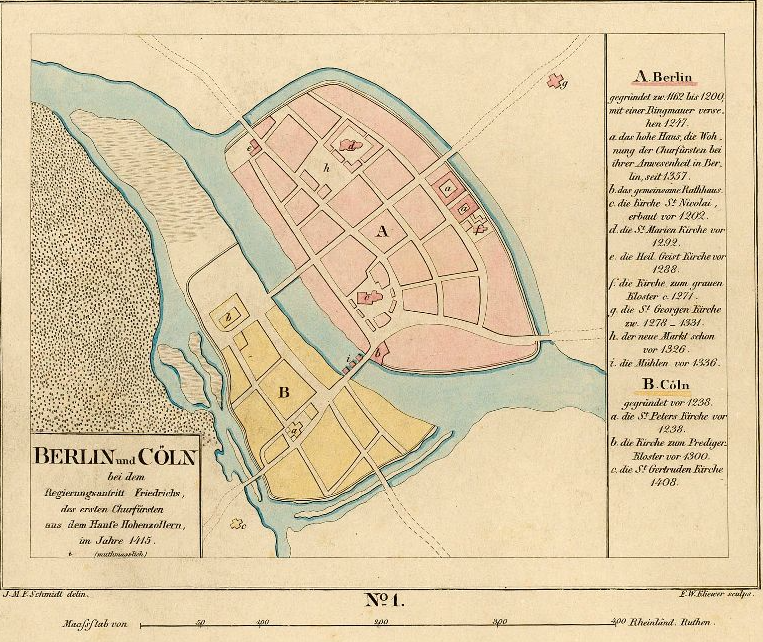

The answer to this question, I believe, is to be found in the urban structure of the city itself. Whether the ideological order of the day demanded that Berlin be either one uniform block or two antagonistic types of liberated entities, this city has always been something quite different: a somewhat messy heap of a hundred or so villages. It is the poly-centricity that physically survived the German Empire, the instabilities of the Weimar Republic, Third Reich submission, Allied occupation, and the subsequent antagonism of Cold War conflict. Before entering the global political arena in the late 19th century and for the far longer time of its existence, the present-day area of Berlin consisted of mixed coniferous forests, marshlands, and far-flung little farming villages. Two of these date back to ancient times: Spandau in the North-West and Köpenick in the South-East, both once founded as hill-forts by the Slavic tribes living here in the 6th century AD. Germanic peoples began to settle in around the 10th century, and archeological findings suggest that many of the villages were developed by bi-cultural communities, a process through which the Slavic populations slowly assimilated into Germanic culture over several hundred years. Many of these settlements form the historical foundations of present-day city districts and local centers.

We think of European cities as growing concentrically throughout the Middle Ages, and so did Berlin, although it was not one city that developed, but several. Its present-day geographical center has, for centuries, been only one among many towns. Although it eventually became the Prussian rulers’ residence, those towns were only incorporated into Greater Berlin in 1920. Prior to this date, many contemporary districts such as Schöneberg, Charlottenburg or Spandau remained independent cities. From this perspective, it isn’t so much the fragmentation that is surprising, as is the assumption of unity. The ‚re-unified‘ city of 1989 became a unified municipality only 70 years earlier. It had been physically divided for more than half of that time.

The idea of a united German nation-state gained traction fairly late in comparison to other European countries. Correspondingly, Berlin took the same amount of time in becoming relevant as its capital city. In a series of armed conflicts in the 1860s and 1870s, the Prussians established themselves as the dominant force within the German Kaiserreich. The history of the 20th century might have unfolded quite differently had they lost any of their more prominent campaigns.

Yet, however much the later regimes tried to reshape the city, the historical structure of poly-centricity predates the modern shape of Berlin by roughly a millennium. And so does the word Kiez, the etymology of which can be traced all the way back to these very first settlements. The term was first documented in Middle Low German (the historic lingua franca of the Baltic Sea region from approximately 1100 to 1600 A.D.), referring to the villages near feudal fortifications inhabited by commoners. From the earliest medieval period of Berlin’s history, the term Kiez was used to refer to the quarters of the common people.

Naturally, the term’s modern appropriations refer to an urban constellation quite different from the medieval one in which it originated. Most likely, its emotional connotations have changed drastically, too, since the passage from Charlottenburg to Spandau meant a day’s journey through the marshlands. For the modern nomad, however the term holds the promise of finding a home, of becoming attached to place. This attachment doesn’t presume an association with an abstract entity. Our allegiance is neither with an entire country nor even the city as a whole but with our most intimate vicinity. The term also reminds us of the myriad small-scale appropriations our neighbors make and have been making in this very place for centuries. It conceives of our individual domestic spaces as extending into the public sphere and hence, as overlapping. What we call our Kiez is the result of these domestications. A space enacted by the constant remaking of our relationship with place and with each other.

Berlin, the urbanized scattering of villages, may come close to embodying this vision of domestic public space.

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank Alexia Elliot and Dawn Nichols for helping me improve the language of this essay.

Further Reading

Wolfgang H. Fritze (Hg.): Germania Slavica. Berliner historische Studien, Two Volumes, Berlin 1980.

Herbert Ludat: Die ostdeutschen Kietze, Bernburg 1936.

„Kiez“ in: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon, Band 10. Leipzig 1907, S. 898–899.

Uwe A. Oster: Preussen: Geschichte eines Königreichs, München 2010.

Hans-Jürgen Rach (Hg.): Die Dörfer in Berlin : ein Handbuch der ehemaligen Landgemeinden im Stadtgebiet von Berlin, Berlin 1990.

Dieser Text steht unter der Lizenz CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 Germany.

© 2020 beim Autor.

DOI: 10.13151/NB.010

VORGESCHLAGENE ZITIERWEISE:

Andreas Lipowsky: Pluri-Polis – The City that is Many, in: Nachbarschaften. Online-Anthologie, hg. von Christina Ernst und Hanna Hamel, 20.7.2020, https://doi.org/10.13151/NB.010.

Weitergehen

gentrification

Mit zunehmender Entmischung und Gentrifizierung bleiben schließlich einige wenige benachteiligte Stadtgebiete zurück, in denen aufgrund mangelnder Ressourcen nachbarschaftliche Beziehungen umso wichtiger zur Bewältigung des Alltags und für den sozialen Austausch werden.

Cold War

„Berlin was not a Cold War story for me.“

fragmentation

Aus der Distanz ist das Erlebte ein Steinbruch, aus dem in mühsamer Knochenarbeit Fragmente von Erlebtem herausgeschlagen und mit anderem Material zu Erzählungen verwebt werden.

tenant

Die dort noch aufgeführten Mieter*innen sind inzwischen von der Gentrifizierungswelle fortgespült worden…

vicinity

…mitten in Kreuzberg, im Partykiez, wie es in der Anzeige hieß, in der Nähe vom Kottbusser Tor, sei aber trotzdem sehr ruhig, absolut idyllisch gelegen…

village

…Nachbarschaft nicht als ein idyllisches Projekt dar, das sich an der Idee des dörflichen Zusammenseins orientiert, sondern als eine Form von Zweck- oder Schicksalsgemeinschaft.

Charlottenburg

Seine Wohnadressen wechseln vom bürgerlichen Charlottenburg über Zwischenstopps in Schöneberg und Friedenau zu einer Kommune, die in einem besetzten Haus beim Potsdamer Platz angesiedelt ist…

medieval

Potsdamer Platz was designed as a city within a city, a theme prominent throughout Berlin, as many present-day districts evolved out of medieval farming villages.

Kiez

Zuweilen sehe ich im Kiez die Frau und ihre Tochter, die mit Vorliebe schwarze Schnürstiefel trugen.

Internet

„Meine Freunde habe ich ja auch nicht im Internet kennengelernt“, sage ich.

the early 2000s

Consequently none of the buildings east of the Philharmony/Federal Library complex and west of the Leipziger Platz existed before the early 2000s.

revolution

Zur jüngeren Vergangenheit gehört die Herrschaft einer „Fremdmacht“ (6), gefolgt von einer religiös-fundamentalistischen Revolution.

forest

…she could feel everything she’d used to look so ardently forward to fall behind her like old-growth redwoods thundering to the forest floor…

moving

Der erste selbständige Umzug des Lebens brachte den jungen K. von der Stolpischen Straße in die Bergener Straße.

tourist

…um einen Austausch und eine Diskussion zwischen AnwohnerInnen, TouristInnen und schließlich den Objekten selbst zu ermöglichen.

Spandau

Rathe ich euch zur Nächstenliebe? Lieber noch rathe ich euch zur

Nächsten-Flucht und zur Fernsten-Liebe!

Friedrich Nitzsche, Also sprach Zarathustra, 1885

Über das Projekt

Die Anthologie NACHBARSCHAFTEN, herausgegeben von Christina Ernst und Hanna Hamel, ist eine Publikation des Interdisziplinären Forschungsverbunds (IFV) „Stadt, Land, Kiez. Nachbarschaften in der Berliner Gegenwartsliteratur“ am Leibniz-Zentrum für Literatur- und Kulturforschung in Berlin. Seit 2019 erforscht das Projekt das Phänomen der Nachbarschaft in der Gegenwartsliteratur und bezieht dazu Überlegungen aus unterschiedlichen wissenschaftlichen Disziplinen mit ein. In der im November 2020 online gestellten Anthologie können Leser*innen durch aktuelle Positionen und Perspektiven aus Literatur und Theorie flanieren, ihre Berührungspunkte und Weggabelungen erkunden und sich in den Nachbarschaften Berlins zwischen den Texten bewegen.

Gefördert durch