Deboarding the U1 underground line at Kottbusser Tor on a Saturday night, I step onto an above-ground platform towering above a roundabout. To the north, through the residential complex hovering over Adalbertstraße, is the center of eastern Kreuzberg – dubbed SO36 after its former postal code. It is also known as Little Istanbul, a tongue-in-cheek reference to its Turkish-German community. It is an area of roughed-up good vibes, populated with inhabitants of all denominations who are fiercely loyal to their Kiez and the independently-minded demographic it attracts. I walk down Adalbertstraße accompanied by a couple of hundred people en route to somewhere close-by. Close-by and yet surprisingly difficult to reach, since everyone is stepping on everyone else’s feet.

Towards Oranienstraße, I pass through and under the Neues Kreuzberger Zentrum (also known as NKZ, or New Kreuzberg Center in English). After passing under the archway, it is worthwhile to look back and up. The building doesn’t have any windows on its northern façade. It was once conceived a prestigious, publicly-sponsored project in the early 1970s, built in anticipation of an inner-city autobahn that was to supplant Oranienstraße. Obsessed with motor vehicles as the time was, urban planning was guided by a vision of convenient access to the city center for the better-off suburbanites. The construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961 disrupted these plans, as they were initially conceived as a collaborative effort between the Eastern and Western administrations of the late 1950s. Kreuzberg successively developed into a center of bohemian culture during the following decades and, even today, the area between the underground line and Oranienstraße still buzzes with commercial and residential life. In fact, it is particularly lively at this hour of the night. Crossing Oranienstraße, however, I find myself in an astonishingly calm residential area. The sudden absence of fellow night crawlers is so striking, I almost feel relieved when I pick up my friend in this eerie Hinterland and we turn back to join the partyfolk. I would normally be hesitant to point to the supernatural for explanation. In any case, ever since it has become my conviction that the district is haunted. Haunted by the specter of a phantom wall.

Much of the widespread interest in today’s German capital derives from its unique fate during the Cold War. The city of Berlin is making significant efforts to preserve that memory in museums, some of them recreating the experience of the division on the sites of the fortifications themselves. Funded and sustained by public institutions, this memorialization assumes that the relevant historical events are complete and set-apart from the living city. Yet in many locations across town, the lingering effects of the Wall, although physically disassembled, refuse to be stored away in museum space. To the contrary, the Wall’s presence forms a curious clandestine border territory in densely populated areas.

Etymologically, the term ‚border‘ denotes the concept of an area defined by its vicinity to another territory. Before the advent of the nation-state, borders were transitional spaces between two kingdoms, peripheries of two realms at once. They were marked by their in-betweenness, in contrast to a frontier, the modern, militarized edge between two spheres of influence. As indeterminate areas, most people would not have traveled there, and, if they did, they’d have preferred to travel through them than to them. Today, while the frontier has been removed in Berlin’s inner city, a border still remains. If only to encourage late night adventurers to turn back and remain in familiar territory.

Map 2: Rathaus Neukölln, Phantom Wall in Red © OpenStreetMap, Open Database License

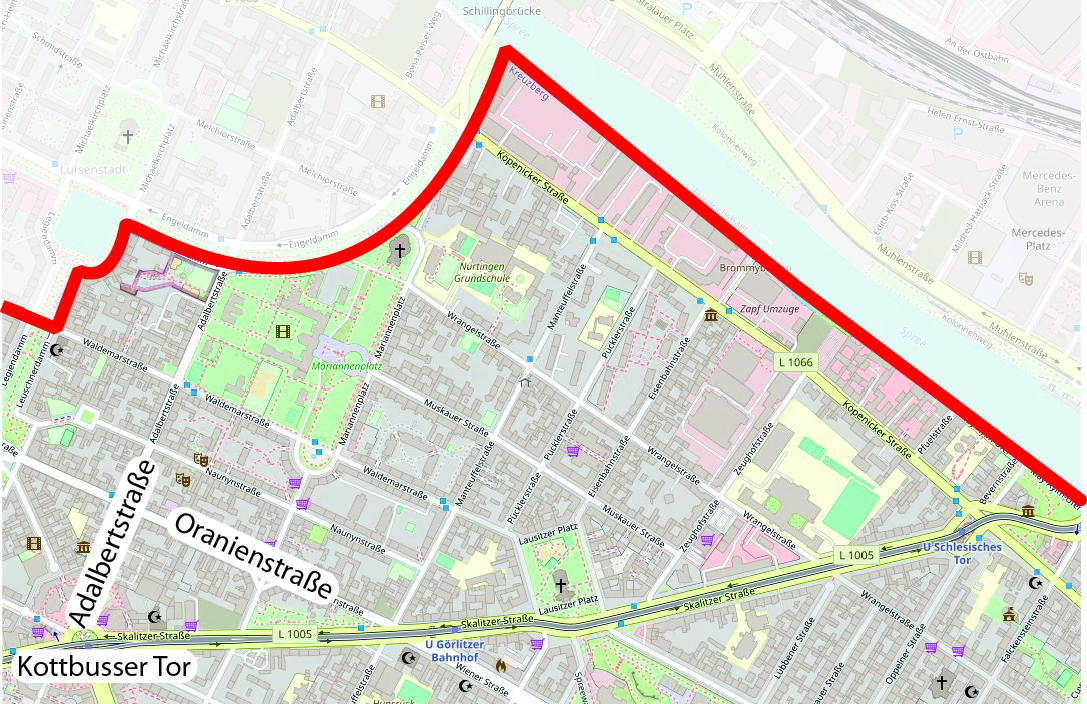

Even though I moved to this town four years after the fall of the Wall, I have reproduced the former Wall divisions throughout my life. Growing up in West Berlin, I have almost always moved in the border area from within the former West. This persistence of movement patterns is not exclusive to Kreuzberg. The phenomenon can be experienced all along the former border — whether one believes in ghosts or not. Over the years, I have had a couple of friends who lived in the Neukölln part of this strip between the underground line and that long-fallen Wall (Map 2).

I got off at Rathaus Neukölln station innumerable times and walked north toward Weichselplatz and the area south of the canal. Still, up until I began preparing to make notes for this essay, in the 16 years of being an inner-city resident, I had been beyond the canal only twice.

I wonder if there may be long-time residents still living in this area who have never crossed one of these bridges and stepped beyond the demarcation line.

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank Alexia Elliot and Dawn Nichols for helping me improve the language of this essay.

Further Reading

Jürgen Enkemann: Kreuzberg. Das andere Berlin. Berlin 2020.

Hanno Hochmuth: Kiezgeschichte. Friedrichshain und Kreuzberg im geteilten Berlin. Göttingen 2017.

Kathrin Chod/Herbert Schwenk/Hainer Weisspflug: Berliner Bezirkslexikon Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg. Berlin 2003.

Dieser Text steht unter der Lizenz CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 Germany.

© 2020 beim Autor.

DOI: 10.13151/NB.012

VORGESCHLAGENE ZITIERWEISE:

Andreas Lipowsky: Walking towards the Phantom Wall, in: Nachbarschaften. Online-Anthologie, hg. von Christina Ernst und Hanna Hamel, 21.7.2020, https://doi.org/10.13151/NB.012.

Weitergehen

Kottbusser Tor

weil mit magnetlesern zwei kumpels von ihm bereits das ganze

geld abgenommen wurde. drüben am kotti, logisch, wo sonst.

the Cold War

Most notably, during the Cold War, Berlin had to simultaneously perform as the outpost of the ‚free‘ capitalist world as well as the prime example of a territory ‚liberated‘ by the socialist revolution.

vicinity

Ähnlich nahe, also lediglich durch einen kleinen Leer- bzw. Luftraum getrennt, scheinen sich auch die beiden Figuren zu sein, die sich am geöffneten Fenster stehend unterhalten. Diese Nähe spiegelt die prekären Wohnverhältnisse der Nachkriegszeit wider, die in einem weiteren Satz kommentiert werden.

border

In Frankreich zeichne ich ungefähre Deutschlandkarten auf Bierdeckel, um zu veranschaulichen, dass le mur de Berlin zwar Berlin teilte, die DDR aber auch noch eine Grenze zur übrigen BRD hatte.

the canal

…welchen besonderen Charakter abgerockte Gründerzeithauseingänge und verregnete Hinterhöfe besitzen oder wie kontemplativ die Stimmung am nächtlichen Landwehrkanal sein kann.

periphery

Der (unterstellte) Widerstreit von Kunst- und Meinungsfreiheit auf der einen und political correctness bzw. „Zensur“ auf der anderen Seite wurde so mit dem Gegensatz von Zentrum und Peripherie verschränkt…

Oranienstraße

Ebenso ließe sich pointenreich schildern, wie Zuse die Arbeit im Industriehof in der Oranienstraße 6 bei täglichem Fliegeralarm unbeirrt fortsetzte.

Wenn dein Nachbar hungert, kommen seine Mäuse in deinen Keller.

Hans Kasper, Nachrichten und Notizen, 1957

Über das Projekt

Die Anthologie NACHBARSCHAFTEN, herausgegeben von Christina Ernst und Hanna Hamel, ist eine Publikation des Interdisziplinären Forschungsverbunds (IFV) „Stadt, Land, Kiez. Nachbarschaften in der Berliner Gegenwartsliteratur“ am Leibniz-Zentrum für Literatur- und Kulturforschung in Berlin. Seit 2019 erforscht das Projekt das Phänomen der Nachbarschaft in der Gegenwartsliteratur und bezieht dazu Überlegungen aus unterschiedlichen wissenschaftlichen Disziplinen mit ein. In der im November 2020 online gestellten Anthologie können Leser*innen durch aktuelle Positionen und Perspektiven aus Literatur und Theorie flanieren, ihre Berührungspunkte und Weggabelungen erkunden und sich in den Nachbarschaften Berlins zwischen den Texten bewegen.

Gefördert durch